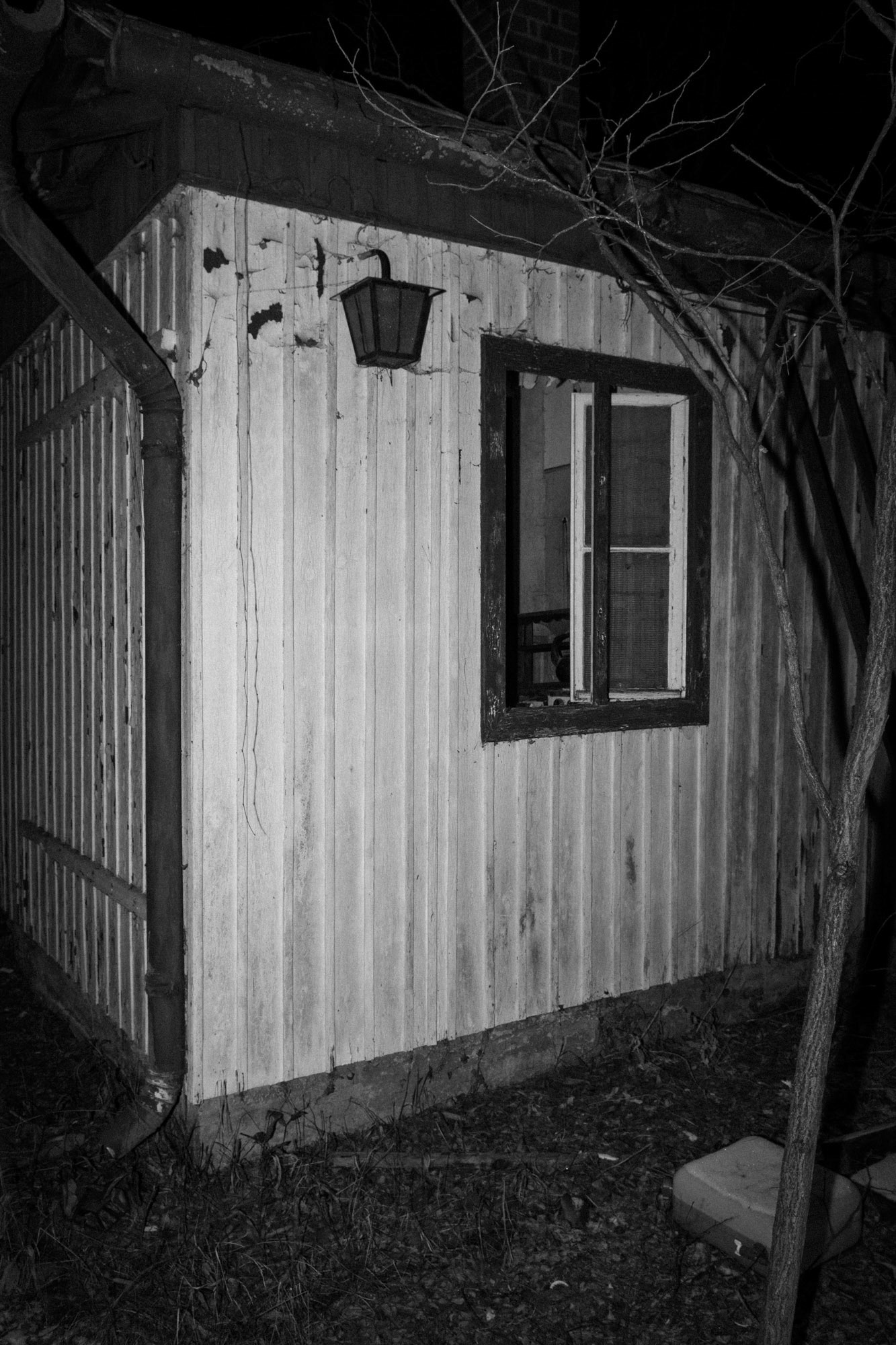

The summer house is still there. It stands there. Like an in-between world that no longer turns, while to the right and left everything stoically goes its steady course. This is the real world. In it, it doesn't matter what I do, whether I'm there or not. It does not live from me. It just keeps on turning, regardless of anything else. The summer house, however, stands in the in-between world which exists only through me and which stops at the end of my imagination. A time of memory. An eternal time. A snow-covered time.

1988

It is a June day. Not yet as hot as in high summer, but already blindingly bright and warm. The wind cools the air. That's how it might have been. At least that's how it is in my memory. This picture stands motionless before my inner eye, half indistinctly. Grandpa Herbert shows my mother the summer house and the big garden with the huge strawberry bed. The two of them are standing somewhere to my right. My mother has shoulder-length, pitch-black hair. I can't turn my head to see her. My memory won't allow it. But I can see her black hair in the old photograph. I lie in the garden on a metal camping bed that is covered with a hard, flower-patterned fabric and look up at the blue sky. The scratchy fabric is attached to the metal frame of the bed with steel springs, and every movement of my body makes a squeaking sound. So, I try to lie calmly on my back while thinking that the eight weeks of summer vacation I will spend in the summer house seem like an eternity.

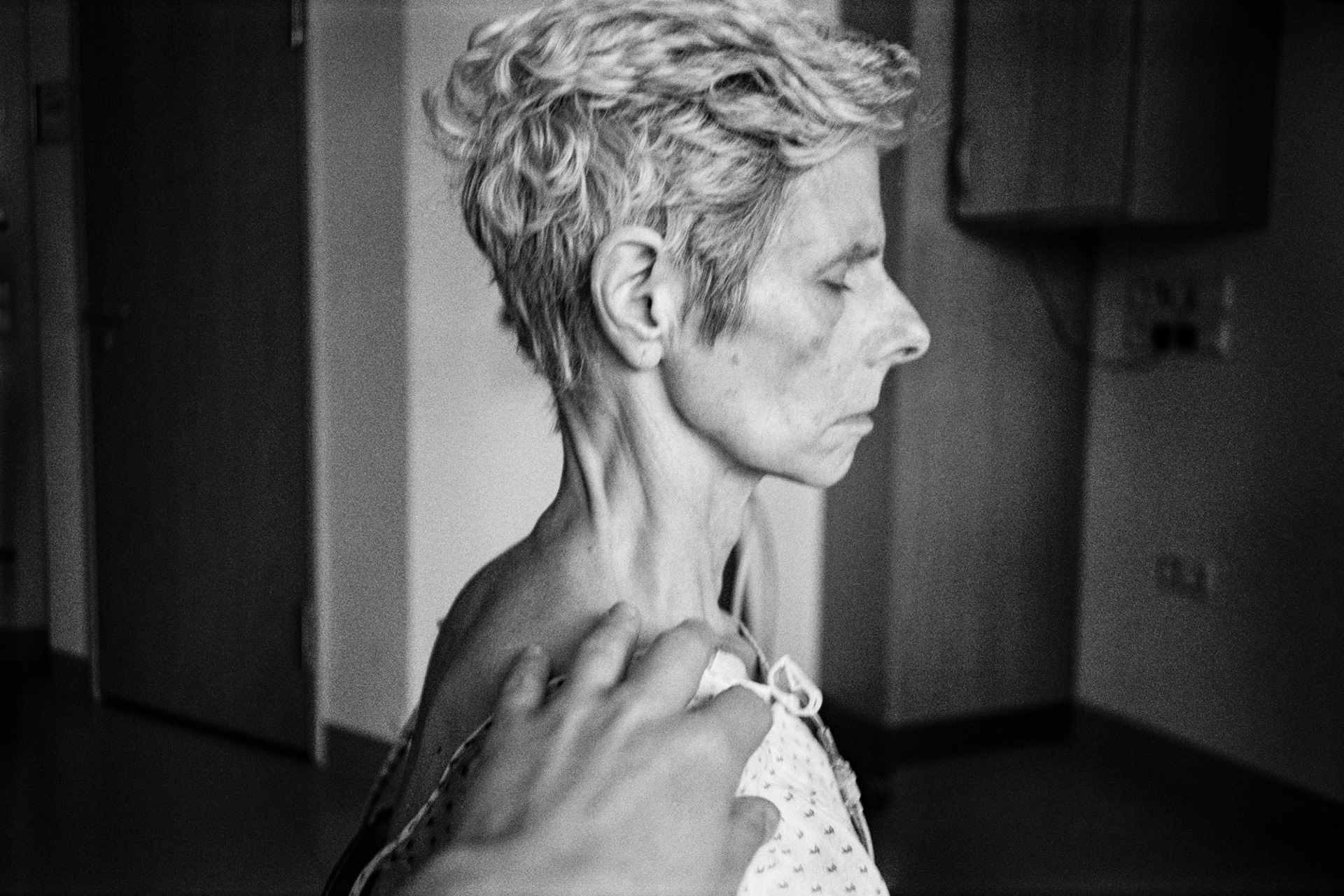

When my mother was diagnosed with cancer, I began photographing her. This marked the beginning of my journey with photography. It was an attempt to create something that would connect us—a way to stay close and capture the process that was changing her. I wanted to be near her and create a space where the unspoken could find expression. But it wasn’t my mother who passed away first; it was my father, who died a year later. It was as if he couldn’t bear the thought of watching my mother die, and so he chose to leave before her.

At the same time, I found myself returning more often to our old summer house. It felt like stepping into a world where death didn’t yet exist. But the house had been abandoned, neglected since we had left. Surrounded by well-maintained properties, it stood in decay, slowly becoming a ruin of my past, crumbling a little more with each visit.

After my mother’s death, I discovered old films and photographs in the attic. Among them was a roll of film she had taken when I was a toddler. Many of the frames were only partially exposed — the flash had fired, but the camera’s sync was misaligned. One half of each image was vivid and clear; the other was consumed by darkness, obscured by the shutter. These photographs offered a window into the past — a past I had lived but couldn’t remember, as I was only a baby. Yet the glimpse they provided was fragmented, incomplete, swallowed by shadow. It felt as though the blackness wasn’t just obscuring the memory but devouring it.

At the same time, I found myself returning more often to our old summer house. It felt like stepping into a world where death didn’t yet exist. But the house had been abandoned, neglected since we had left. Surrounded by well-maintained properties, it stood in decay, slowly becoming a ruin of my past, crumbling a little more with each visit.

After my mother’s death, I discovered old films and photographs in the attic. Among them was a roll of film she had taken when I was a toddler. Many of the frames were only partially exposed — the flash had fired, but the camera’s sync was misaligned. One half of each image was vivid and clear; the other was consumed by darkness, obscured by the shutter. These photographs offered a window into the past — a past I had lived but couldn’t remember, as I was only a baby. Yet the glimpse they provided was fragmented, incomplete, swallowed by shadow. It felt as though the blackness wasn’t just obscuring the memory but devouring it.

"Der letzte Schnee (2022) ist die intime Schwarz-Weiß-Geschichte eines Sohnes, der den langsamen, krebsbedingten Todeskampf seiner Mutter miterlebt, und die Folgen dieses Todes für die Erinnerungen an diese geliebte Person bewahrt. „Wenn ich jetzt an meine Mutter denke, ist das aus der Perspektive ihres Lebensendes, als hätte meine Erinnerung an sie mit ihrem Tod begonnen“, schreibt der Berliner Fotograf Ilja Niederkirchner. Das Projekt artikuliert Porträts der Mutter des Künstlers während ihrer Krankheit und aktuelle Fotografien des Sommerhauses, in dem Niederkirchner einen Teil seiner Kindheit verbrachte, sowie anderer Orte, die mit seiner Familiengeschichte in Verbindung stehen. In der Ausstellung in einer einzigen Bildzeile präsentiert, bildet die Serie eine Art Zeitstrahl des Lebensendes der Mutter des Künstlers, unterbrochen von Flaschbacks. Während er intensive Bilder der Krankheit zeigt, teilt Niederkirchner mit einem Sinn für Diskretion seine Erfahrung eines anthropologischen Universalismus, so schwindelerregend wie unvermeidlich und natürlich, wie der Tod eines Elternteils."

Fotogalerie Friedrichshain